Geology and Mineralogy Gallery of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris

Fluorescent Minerals: When Stones Glow in the Dark

Mineral & Gem 2025: a major international mineralogical exhibition

The History of the Gold Rush in the United States

Discover vanadinite

The Mineralogy of Spain: A Hidden Treasure

The History of the Gold Rush in the United States

When gold changes the destiny of a country

At the turn of the 19th century, the United States was a young nation still undergoing territorial expansion. The economy relied largely on agriculture and trade, while the western territories remained largely unexplored by European settlers.

In this context, the discovery of gold deposits was a transformative event. It attracted not only local populations, but also thousands of migrants from around the world. The gold rush became a symbol of dreams and hope, but also of disillusionment and conflict.

The beginnings: Before the great rush (1800-1847)

Long before the famous California gold Rush of 1848, veins were discovered in the southeastern United States. In 1799, in North Carolina, a young boy found a 7.7 kg nugget in a river. This was just the beginning of a series of discoveries, particularly in Georgia in the 1820s.

These early rushes, however, remained limited in scale and national impact. They nevertheless laid the foundations for gold mining and set a precedent for future events.

1848: The discovery of Sutter's Mill in California

Sutters Mill R. H. Vance, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

On January 24, 1848, a carpenter named James Wilson Marshall, employed by Swiss pioneer John Sutter, made a discovery that would change American history. While inspecting the construction of a sawmill on the banks of the American River near Coloma, California, Marshall noticed shiny flakes in the water. He collected them and had them examined: they were indeed gold.

At that time, California had just come under U.S. control, following the Mexican-American War and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed a few weeks later, in February 1848. This region, still sparsely populated by American settlers, was largely composed of rural lands, former Mexican territories, and indigenous communities.

John Sutter, anxious to protect his land and agricultural projects, initially tried to keep the discovery secret. But the news eventually leaked. At first, local residents quietly flocked to the site. Then, California newspapers, notably the California Star and The Californian, began to relay the rumor. Within months, the news spread across the country, carried by eyewitness accounts, letters, and ships.

The real turning point came in late 1848, when U.S. President James K. Polk officially confirmed the presence of gold in California in a speech to Congress after receiving a sample of the precious metal. This presidential validation captured the public's imagination and legitimized the gold rush.

The discovery of Sutter's Mill thus triggered an unprecedented migratory phenomenon. It marked the starting point of the most famous gold rush in American history, radically transforming California and redefining the economic, demographic, and geopolitical balance of the United States.

1849 and the arrival of the "Forty-Niners"

Au-dessus du col Chilkoot pendant la ruée vers l'or en Alaska National Archives and Records Administration, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The year 1849 became emblematic with the massive arrival of tens of thousands of prospectors, dubbed the "Forty-Niners" in reference to this key date. Motivated by stories of quickly amassed fortunes, these men—and a few rare women—embarked on an adventure as uncertain as it was perilous, hoping to find gold and change their destiny.

Migrants are flocking from all directions. Residents of the East Coast of the United States, as well as citizens of Latin America, Europe (notably Germany, France, Ireland), and China are undertaking the long journey to California. Three main routes are available to them: crossing the continent by land via the Oregon Trail or Santa Fe Trail, sea routes around South America via Cape Horn, or the combined passage via the Isthmus of Panama, which involves crossing on foot in difficult tropical conditions before taking a boat back to San Francisco.

The journey was fraught with pitfalls: illness, shipwrecks, banditry, and exhaustion. The luckiest arrived after several months, hungry but full of hope. In California, they discovered a land in turmoil, without solid administrative structures and a makeshift society where the law of the strongest often reigns.

The number of gold prospectors exploded: it is estimated that in 1849 alone, more than 80,000 people arrived in California, transforming previously deserted areas into boomtowns. These newcomers were not all seasoned miners; many had never handled a shovel or a sieve. This human diversity gave rise to a cosmopolitan society, driven by ambition, uncertainty, and the desperate quest for quick riches.

This massive influx marked a major turning point in the history of the American West, and laid the foundations for the rapid transformation of California into a major economic and political center of the United States.

San Francisco: Birth of a Metropolis

Écluse à or en bois en Californie entre 1890 et 1915 Original téléversé par Lordkinbote sur Wikipédia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Before 1848, San Francisco—then known as Yerba Buena—was a modest port village nestled on the California Bay. Sparsely populated, it had only about 1,000 inhabitants, living mainly from maritime trade, fishing, and ranching. But the discovery of gold at Coloma and the massive arrival of the "Forty-Niners" would forever change the destiny of this small town.

By 1849, San Francisco had become the main gateway to the Sierra Nevada gold fields. Thanks to its ideal geographical location, it welcomed ships from all over the world, particularly those from the East Coast, South America, Europe, and Asia. The port transformed into a gigantic crossroads where hundreds, then thousands, of gold prospectors, traders, adventurers, and speculators disembarked every day.

Population growth was meteoric: between 1848 and 1852, San Francisco's population grew from a few hundred to over 36,000. Infrastructure struggled to keep up with this frenetic pace. Entire neighborhoods were hastily constructed, often with makeshift materials. Tents, wooden, or canvas shacks sprawled across the surrounding hills. Fires—frequent in a city built mostly of wood—regularly ravaged the precarious structures, but each time, the city was reborn with greater fervor.

With the explosion of commercial activity, banks, hotels, gambling houses, saloons, and brothels sprang up at a frenetic pace. The city became a place of contrasts: rapid prosperity for some, poverty and violence for others. Disorder often reigned: crime increased, courts were overwhelmed or nonexistent, and justice was sometimes meted out expeditiously by self-appointed vigilance committees.

Despite these challenges, San Francisco quickly established itself as the economic, cultural, and political center of California. It became the first city to embody the dynamism and exuberance of the burgeoning West. Its growth alone symbolizes the impact of the gold Rush: a brutal but irresistible transformation, intertwining opportunity, chaos, and modernity.

Life in the mining camps

Exploitation minière hydraulique à Dutch Flat, Californie, entre 1857 et 1870 Original uploaded by Lordkinbote Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Daily life in the mining camps of the California gold Rush was marked by harshness, unpredictability, and a striking mix of hope and disillusionment. These camps, hastily erected as close as possible to the gold deposits, were often temporary and built with whatever was at hand: tents, wooden cabins, canvas or branch huts. They could disappear as quickly as they had been created, depending on the discovery—or not—of new veins.

Living conditions there were particularly harsh. Hygiene was basic, sanitation was virtually nonexistent, and diseases—such as dysentery, cholera, and scurvy—were rampant. Access to clean water, fresh food, or medical care was limited. Life was organized around a grueling routine: gold prospectors worked from sunrise to sunset, in mud, icy river water, or under a scorching sun, wielding sieves, shovels, and pans.

Despite these difficulties, the mining camps were also places of intense sociability and cultural abundance. A remarkable ethnic diversity characterized these camps: one encountered Americans from the East, Mexicans, Chileans, Chinese, free or enfranchised African Americans, and even a few newly arrived Europeans. While this diversity sometimes encouraged exchanges, it also generated tensions and discrimination. Some groups were excluded from prospecting areas or subjected to specific taxes, such as Chinese or Latin American miners.

The absence of formal law in many mining areas left room for an often improvised justice system. Disputes over gold plots were frequent, and thefts, sometimes violent, commonplace. In response, miners established their own codes, elected camp judges, or formed committees to enforce a semblance of order.

Distractions were not lacking, however: gambling, strong alcohol, traveling shows, impromptu dances, and reading newspapers or letters received from their homeland punctuated the long weeks of labor. These moments of escape provided essential respite from a grueling daily routine.

In short, life in the mining camps reflected all the ambivalence of the gold rush: a world of promises and illusions, of encounters and conflicts, of sweat and hope, in which dreams of fortune rubbed shoulders with the harsh reality of existence on the margins of the civilized world.

Economic, social and environmental consequences

Carte des États-Unis (ruée vers l'or) de 1852 par Duvotenay - Geographicus - États-Unis Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The California gold Rush, which began in 1848, had profound and lasting consequences for the development of the United States. It not only transformed the country's economy, but also reshaped its social landscape and caused environmental upheavals of unprecedented proportions.

Economically, the gold Rush injected considerable quantities of the precious metal into American and international financial systems. Between 1848 and 1855, it is estimated that more than 750,000 kilos of gold were extracted from Californian soil. This windfall helped finance Western infrastructure, strengthen the nascent banking system, and consolidate the United States' position in international markets. San Francisco became a vibrant commercial center, roads and railroads were laid, and the state of California, admitted to the Union in 1850, quickly established itself as a regional economic powerhouse.

From a social perspective, the gold Rush triggered an unprecedented mass migration. Hundreds of thousands of people—from all walks of life—converged on California, disrupting the territory's demographic balance. This diversity gave rise to a multicultural society, marked by the intermingling of languages, religions, and customs. However, this mix was also accompanied by tensions, inequalities, and violence. Indigenous populations were the first victims of this expansion: displaced, massacred, or decimated by disease, their numbers fell dramatically. At the same time, racial discrimination intensified, particularly against Chinese, Latin American, and African American workers, who were often relegated to the most menial tasks or excluded from certain rights.

Environmentally, the impact was just as considerable. Intensive mining, whether artisanal or mechanized, led to rapid ecosystem degradation. The digging of rivers, the use of mercury to amalgamate gold, massive deforestation, and soil erosion caused the destruction of vast natural areas. Hydro-extraction techniques, in particular, caused real devastation, altering the course of rivers and burying farmland under rubble.

Thus, while the gold Rush was a powerful engine of growth and innovation, it also left behind a mixed legacy: rapid economic expansion, but at the cost of severe social injustices and lasting impoverishment of California's environment. This pivotal moment in American history thus embodies both the dream of prosperity and the excesses of the conquest of the West.

What's next? More rushes across the United States

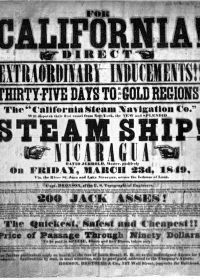

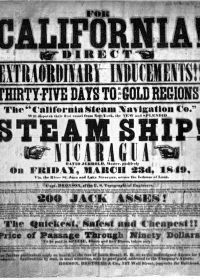

Prospectus sur la ruée vers l'or en Californie ArwinJ, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Although the California gold Rush is the most famous, it was not an isolated phenomenon. Other gold discoveries punctuated American history during the 19th century, each causing a similar shockwave: sudden migrations, rapid economic growth, then resource depletion and decline. These events contributed to the gradual settlement of the West and the assertion of federal sovereignty over previously poorly integrated territories.

Here are the major gold rushes in the United States:

- Colorado (1859)

Known as the "Pike's Peak gold Rush," it attracted nearly 100,000 gold seekers to the Rocky Mountains. - Montana (1862)

gold deposits were discovered near Grasshopper Creek, leading to the founding of towns such as Bannack and Virginia City. - Idaho (1860–1863)

Several successive rushes boosted the region's economy, particularly around Pierce and Boise Basin. - South Dakota (1876)

The discovery of gold in the Black Hills, sacred lands for the Lakota, leads to a rush that causes serious conflicts with the indigenous populations. - Klondike, Alaska (1896–1899)

Although located in the Canadian Yukon, the massive influx of American prospectors gave this rush a major cross-border dimension, symbolized by the city of Nome in Alaska.

Each of these rushes follows a characteristic cycle: a chance mineral discovery, a mass migration of prospectors, explosive growth of settlements and local economies, and then inevitable decline as resources were depleted. These episodes not only shaped the economic landscape of the West, but also fostered the lasting establishment of infrastructure, administrations, and populations in previously sparsely populated or self-governing territories.

Heritage and current fascination

The story of the gold Rush embodies one of the great founding narratives of the United States. It blends hope, individualism, and territorial expansion, as well as violence, racism, and exploitation. It leaves an ambivalent legacy, in which the fascination with adventure and quick fortune coexists with the painful memories of a brutal era. Today, it still informs American popular culture, from Westerns to cinema, and serves as a reminder of the tumultuous origins of the American dream.

mineraly.fr

mineraly.fr

mineraly.co.uk

mineraly.co.uk

mineraly.com.de

mineraly.com.de

mineraly.it

mineraly.it

mineraly.es

mineraly.es

mineraly.nl

mineraly.nl

mineraly.pt

mineraly.pt

mineraly.se

mineraly.se